How does one enact love in the world? Rabbi Moshe Cordovero (aka the Ramak, 1522-1570) borrows his answer from the Talmud, Tractate Shabbat: by caring for children, visiting the sick, giving tzedakah, offering hospitality to strangers, burying the dead, celebrating weddings, and helping friends make peace.

To this traditional answer, Ramak adds a kabbalistic twist. Each of the actions, he says, directly affects God. Playing on a verse in Shir HaShirim (Song of Songs), he says that the Shechinah (God’s close-at-hand motherly aspect) is sick with love, desperately wanting us to recognize her presence. When we visit the sick, and uplift them, we also uplift the Shechinah.

In modern language, Ramak teaches that love happens when we do acts of love. When we attend to the sick, they are attended to. Similarly, spirituality happens when we are spiritual. God’s presence is present when we open our thoughts and feelings to it.

Sometimes, even in our own eyes, we fall short in acts of love. We may worry that our capacity to give and thus create love is not as full as it could be. This week of Chesed is a wonderful week to examine our attitudes around specific acts of love. Why, for example, might we fear or resent a particular practice? How have we been wounded in that area? How can we bring more attention, spirit and Divine presence into that area? How can we receive and even welcome Shechinah more fully?

***

In some of his writings, Sigmund Freud describes the human psyche as composed of id, ego, and superego. The id is a set of natural, passionate, un-socialized drives. The ego mediates between the id and the demands of the social world, channeling the id constructively. The superego judges the ego’s work, using criteria taught by parents at the early stages of socialization.

When Rabbi Moshe Cordovero (aka the Ramak, 1522-1570) discusses the sephirah of gevurah, he presents ideas similar to Freud’s. Our human psyche includes a yetzer hara. Traditionally translated as “evil inclination,” the yetzer hara is actually a set of instinctive drives that can be channeled well or poorly.

When the yetzer hara is poorly directed, gevurah, judgment, is aroused. The superego speaks within a person, offering self-criticism. The Divine Parent also judges the person negatively. But simple awareness of negative judgments is not sufficient to redirect the yetzer hara.

Only chesed, love for others, can set a person on the right course. Only the ego’s appreciation for social life can channel the yetzer hara to a constructive end. Suppose, for example, the yetzer hara is aroused by materialism. Add in chesed, and a person may amass wealth so that they can share it with others. Suppose the yetzer hara is erotically aroused. Add in chesed, and a person may use their passion to bond with a partner.

In other words, teaches the Ramak, effective gevurah, discipline, can only be created with chesed, love.

Where in your life have you tried to create discipline and failed? How might love help you in that area?

Image: thefamilygroove.com

***

Tiferet: Beauty, Truth, Balance

Tiferet: Beauty, Truth, Balance

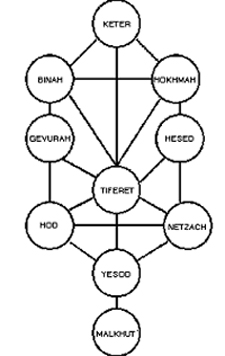

The most famous map of the sefirot shows keter (crown) at the top. Some see keter as a way to begin spiritual practice, an attribute of openness, like a mind emptied in order to receive new ideas. Perhaps students should cultivate keter as they begin a course of study.

The same map places tiferet at the center, as if it is the heart of spiritual practice. Literally, tiferet means “beauty,” but is sometimes translated as “balance” or “truth.” Some say it represents an ideal approach to human relationships, balancing chesed (love) and gevurah (judgment).

When the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) instructs teachers, he admonishes them to cultivate the attribute of tiferet. On the one side, geuvrah involves the ability to make fine distinctions, organize ideas correctly, and grasp logical implications. On the other side, chesed involves welcoming others.

Psychologist Carl Rogers teaches: offer a relationship in which a person feels affirmed, and they will change for the better. Learning requires both sides blended in tiferet-balance. When a teacher offers appropriate chesed-love, a student’s gevurah-judgment is activated for the best.

The Ramak says, “if you hold yourself to be superior to your student, you cause the energy of the sefirot to flow backwards.” Ideas retreat from the heart, where they can be actualized, back into keter, the empty space of nothingness!

The Ramak’s teaching on tiferet can be stated more simply, using my mother’s straightforward prose. She taught that more experienced, intellectually gifted or culturally comfortable people must adapt to those less so. Teachers must reach out at the learner’s level, and not expect students to already be there.

How can you reach out from within your places of comfort, security and expertise?

***

Netzach: Endurance and Victory

Netzach: Endurance and Victory

Baruch She’amar, a traditional morning prayer, praises God by saying “Baruch…kayam lanetzach.” The phrase could be translated as “Bless the One…who rises to victory” or “…who endures for eternity.” The translations are not completely distinct; in long distance races, endurance makes victory possible. And perhaps there are some metaphorical long distance races in which endurance itself is victory.

ALEPH rabbinic students David Aladjem, Kellie Conley Scheer, and Heena Reiter suggest this is the nature of the spiritual quest. The goal is to accept change with awareness and an eye for spiritual and ethical growth. In this quest, endurance is victory. They write:

Would you run a race if there were no finish line? Didn’t our parents say, “Well, when you’re a grownup…” a few hundred times in our youth? When are we grow up? Will there ever be a final point in time when we have finished growing and we are “grown” up? Growing is evolving. It is running a race to which there is no finish line. We may walk through a few places catching our breath and try our hardest to spring through others, but stopping altogether to declare one’s self grown is giving up on ourselves.

We may never call ourselves fully “grown,” but sometimes we want to say we are tired. Tired of facing challenges, untangling personal lessons, taking responsibility for all our thoughts and feelings.

About this, the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) speaks quite concretely. Torah scholars, i.e. spiritual seekers, need practical sustenance: food, sleep, and other people doing nice things for them.

In what ways do you need self-care? In what ways might caring for others be part of your own self-care?

In honour of Boston’s long distance runners, victims of terrorism, first responders, and continuing helpers. Image: Boston Marathon 2013, washingtonpost.com.

***

Hod: Gratitude & Majestic Beauty

Hod: Gratitude & Majestic Beauty

The Hebrew word Hod can mean “splendor,” in the sense of “majestic beauty.” Hod can also mean gratitude. Majestic beauty and gratitude can be connected in a single spiritual moment, as beauty brings us to gratitude. Experience offers examples of such moments, and linguistic wordplay reinforces them.

Even on a difficult day, a glimpse of natural beauty can shift our consciousness. A passing butterfly or a falling cherry blossom can cause us to cry out, “I’m grateful for this gift of life!”

When people disappoint us, causing our faith in humanity to wane, a work of art can restore us. Artists reflect, critique, and transform. The arts remind us that the human soul can grow in refinement. They encourage us to be grateful for our intellect and emotions.

The Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) implies that Hod offers two different pathways to God. Hod, he says, is among the “limudei HaShem.” (Isaiah 54:13). The phrase limudei HaShem can be translated as “students of” HaShem as well as “studies of” HaShem – and both translations apply to Hod.

As a metaphorical student, Hod carries a bit of the energy of its teacher. In other words, Hod is an emanation of Divine energy. To us, it appears as the splendor of God. Majestic beauty is thus a direct vision of the Presence of God.

As a metaphorical study, Hod is an attitude of approach. A good researcher studies with appreciative humility, aka gratitude. Gratitude is a receptive posture that allows us to recognize the Presence of God.

In your daily routine, and on your daily route, can you find places where majestic beauty opens your heart to gratitude? What variations can you make to increase your opportunities?

Image: www.daviddarling.info

***

Literally, the Hebrew word yesod means “foundation.” It’s helpful to think of yesod as “foundational energy.”

Plato offers a theory about foundational energy in the human psyche. In his dialogue Symposium, eight drunken men and one imaginary woman discuss the nature of love. They speak about love of family, friends, lovers, community, arts and more. All these, they conclude, are expressions of a single drive: the yearning to bring beauty into the world. People yearn to reach beyond themselves, into the realm of the gods, so to speak, for new inspiration. A passion for reaching up, reaching in, and reaching out: that’s “Eros,” a divine messenger and the foundation of human civilization.

For the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570), Yesod is this foundational energy. Making an analogy between God’s creation and human procreation, he sees Yesod as the energy of the father, providing a seed of inspiration. Ramak cautions men not to waste the Yesod entrusted to them, and to express it in good marital relationships.

Yesod, of course, refers to more than this physical metaphor. Yesod expresses God’s desire to fill us with Divine Spirit, so that we can become creative beings. We are always pregnant with meaning. Beauty can burst through at any moment, on any level of consciousness.

What foundational energies yearn to find expression in your life?

And where can you notice beauty being born?

Image: Eros stringing his bow, Roman copy of Greek statue by Lysippos c. 4th BCE, theoi.com

***

Malchut-Shechinah: Divine Mother

Malchut-Shechinah: Divine Mother

Though a human mother might forget her children, I never could forget you. See, I have engraved you on the palms of My hands. (Isaiah 49:14-16).

Opening to Shechinah is the last station on the seven-week journey of the Omer. This last week represents an opportunity to experience emotionally a subtle truth about God.

Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) imagines Shechinah as an archetypal image of Mother. No matter how much or how little each of us was loved by our real mothers, Shechinah sustains us spiritually with unconditional love. Held by love, we develop the confidence and courage to support one another in difficult times.

Just as Shechinah, a facet of God, may not be like your real mother, so God the creator may not be like any created thing. For example, says the Ramak, we are taught to approach God with yirah. Yirah can mean either “fear” or “awe”; so which is the proper attitude towards God? Normally, we fear concrete things like suffering, violence, or death. But God is not like these things. God does not destroy us; God sustains us. Thus, we should approach God with unique awe, not ordinary fear.

Perhaps we have reflected deeply on the sefirot during this Omer period. If we have paid attention to these psychic vessels for shaping and holding divine energy, we may be increasingly aware of spiritual thoughts and feelings. These thoughts and feelings, however, are not God. They are only reflections of God’s power, messengers announcing God’s existence, forms of consciousness turning us towards God’s presence.

Who in your life has held you with unconditional love? How have they helped you understand that you are more than your fears? How have they alerted you to God’s presence? And how will you thank them this Mother’s Day?

— Image: Florence Owens Thompson by Dorothea Lange

Beautiful.

Thank you Rabbi, for the explanation of “yetzer hara.” It would resemble the way of Creator, Hashem of The People. Native elders, grandmothers and grandfathers will tell youth when they error: “That is just good coming out in a bad way.” The emphasis, with its great gentleness, is that one might work so good comes out in a good way, as though one understood that one is pure and at any moment, one can choose to honour and to build on such purity. It is nice we are the same. I also appreciate when a Rabbi explains something of kabbalah, When I went to shul in Regina, Saskatchewan, (Beth Jacob), our Rabbi Parnes, also spoke about such ideas during the Counting of the Omer. I enjoyed it, for even when he said the word Kabbalah the day in his office when I first met him, his voice had great love in it for whatever he understood or knew of that Way. For me though, perhaps because I am just reading the Tanach, studying languages, studying maps of the homeland for weather patterns and rivers and terrain, learning kashrut, learning some politesse about my innate ability to interfer in the worlds of others (in a well-intentioned benevolent way, I submit), arranging life so it works– in such an infancy I find each time I see a book with circles in it, I try, but it bores me stiff. “Did Bubbe 200 yrs ago need to study this, or the other one?(They left even earlier). I can see why the sages invented this to be studied at fifty or whenever by the men and the women– those women who having no brothers, ask for and receive the inheritance, (that strange chapter in Devarim).” I am very grateful to have people who make kabbalah simple, especially they who are of the authority to speak what it true of it. I do apologize for my length, my rudeness towards a sacred path and the untraditional interpretation of Torah at very end (which has no validity according to what I have read so far.) Of the last though, because I have been so long away, though I develop and reorient, I will never be as those others whose ancestors did not leave, or those who joined after my mothers people and my fathers left. I am able though, to clearly perceive the beauty of soul of those who belong, in a way they cannot sometimes. And as is, when I feel sad about how it is I am, I say, “Well, maybe Rak Lakish is really the best you are, Katherine,at best, but maybe you will one day, prove that irritating bit of gravel, some Jewish oyster uses to create a pearl.”